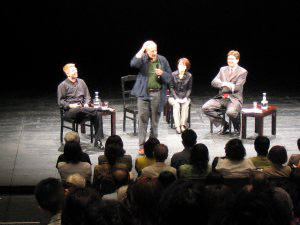

| “Falstaff” Opera Talk Held |

| Welcome to our OPERA TALK review. As the last opera talk of 2003/2004 season, Thomas Novohradsky featured the production of “FALSTAFF” with Dan Ettinger (Conductor) and Jonathan Miller (Stage Director). Hope you will enjoy our “Falstaff” more with this review. Performance is coming soon. Don't miss it!! |

|||||||||||

(*The article written by Jonathan Miller in The New York Review of Books.) |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

Thomas Novohradsky (TN):

Both has

very unique career, both started completely somewhere else to became what

they are now. (To Mr. Ettinger) Tell us about your background. Dan Ettinger(DN): I was probably not a very serious conductor, as I've never studied conducting. I studied music as a singer. As a young pianist, like everyone studied piano in this generation, I entered a music high school. I started singing in high school chorus, then developing my voice started the singing career that lasted about 9 years, and singing most of the liric Barione repertoire, Figaro, Conte, Papageno, Malatesta, Belcore. During this period also playing the piano and coaching other singers, which was a nice combination between two professions both sides of the world, singing and coaching. Working with many conductors, you can learn very much from them both what to do and especially what no to do. Then I simply got an offer by New Israeli Opera, because I am originally from Tel Aviv, Israel, to become a chorus master for the Opera House. Then I really wanted a chance to go into the orchestra pit and conduct an opera later on. So the opera management decided to take the risk, and make me try it. And here I am today with you and hopefully to open the wonderful “Falstaff” in 4 weeks. TN: That was very modest way of telling. In between conducting Israeli Opera and here, you already fest conductor with Staatsoper Berlin. DE: I was very lucky to had a chance to meet Maestro Daniel Barenboim about 2 years ago, and really established wonderful personal and musical connection with him, which let me be invited to be a house conductor of Staatsoper Berlin and his personal assistant. I am just finishing my first season there and starting two coming seasons. TN: Jonathan, I think you

have one of the most interesting ways to opera. You really didn't start

from the very beginning, you didn't know you want to come opera director?

I went to Cambridge, and by that time, I decided that I wouldn't to be a biologist, I wanted really to study medicine. I had no philanthropic idea, I wasn't particularly interested in helping people. I didn't want to hurt them but I didn't want to help them particularly. I wanted to go into medicine because you can't do experiment on human beings, but nature does them for you and they call an accidents, injuries and illnesses, and when the brain is damaged, you can see something about how the brain works. So I qualified as the doctor, I was for three years at Cambridge studying anatomy physiology, biochemistry, pathology, and I also continuous doing zoology. I must say very important part of my training in Cambridge was my introduction to what we call "Anglo- American Philosophy" analytic, linguistic philosophy. I have no time for what we call "French & German Philosophy". I went into medicine because I was interested in two things, probably more but two important things I continue to be interested in it when I'm doing plays or operas. I was interested in the one hand what goes into nerve system, and I was interested in what comes out the nerve system. In otherwise perception on the one hand and action on the other, and I wanted to know what it was made the difference between an action which we intend to do and an action which simply happens without our controlling it, and what happens when we actually perceive and recognize an object. TN: What accident made you come to the theatre? JM: The accident was I

am as an amusement and as an entertainment for myself I hope for other

people, I would occasionally act funny stuff on the stage, it was an amateur

dramatics in Cambridge was quite important, and from time to time I did

funny acts. By the time I finished my medical training, someone asked

me and three other people, Dudley Moore, Peter Cook and Aaron Benett to

do a show at the Edinburgh Festival. So I went into this show as the holiday

entertainment for myself, I was still working as the doctor by that time. JM:I don't know what makes a good director or a bad director. I don't think any training does you any good at all. It's mostly to do with intuition and keeping your eyes open and seeing what people do. It's exactly the same skills that I learnt of being a doctor. When you are doing diagnosis, you stand at the patient's bedside, you talk to them, you look at them and you examine them and you do tests with your hands and with hammers and pins and so forth. And you keep your eyes open. Well that's all you do as a director. You keep your eyes open. TN:I see you are not a believer in opera jokes and scientific common sense in opera. JM: The two things I'm against in opera or in plays is what has become very fashionable, which is theory, Having being trained as a scientist and a philosopher of science, I know when I'm in presence of real theories, and when theory gets into theatre or literature, it's almost always Franco-German nonsense. And I can't stand it really. It's mostly to do with common sense. If you can find your way to the toilet without advice, you can direct. TN: So by your talent and by your training, you observe the world and bring it to the opera or theatre. JM:I think that if you are doing presentations of behavior, and that's really all that the theatre is, you put on this side of the room people pretending to be people watched by people who are actually people, And the people who are actually there are watching people who are pretending to be them and you can recognize whether they are real or not. It's very simple. TN: The situations and reactions and moves and gesture we everyday actually see. JM: We see them all the time. That's all there is with human beings. We live in a very complicated social environment, in which we represent each other to each other and much of what we do is the expression of things we intend to do and some of the things that we do is the things we don't intend to do. So any spectator of any other person is trying to make a separation between the actions, which are obvious in their intentions, and the actions, which are obscure in their intentions. TN: And what makes us laugh? JM:I think there are many things. There are literally hundreds of theories of humor, And it's the hardest thing to give an accurate description of. I think I was saying to you Thomas the other day there are lots of what we call involuntary activities. Peculiar respiratory convulsions; coughing, sneezing, crying and laughing. Now, some of them are provoked by what we call stimuli. But you see if you said there are two of these involuntary activities

that you can control. You can try not to laugh and you can try on to cry.

And you can try not to sneeze and you can try not to cough. But coughing

and sneezing on the one hand are produced by very different types of approach

to the nervous system. Crying and laughing are produced by situations.

Coughing and sneezing are produced by local stimulation of the mucous

membranes. But I think that there's a very important category of things that make us laugh. And usually it's having brought to your attention what you know anyway at a deep unconscious level. The comedian or the humorist brings it up to the surface and TN: Like what we see everyday? JM: Well, a little narrow area that you'll all recognize. It will differ of course in Japan as it will differ in France or Germany because it all depends on social manners. As I say sneezing happens the same all the world over, every one sneezes in the same way but the same things don't make you laugh. I'll give you an example. I'm very influenced by a great American social observer called Erving Goffman, who talks about the way in which we constantly perform for a potential audience of others, in which there is always the possibility of a faulty performance. And you all know this but there are many performances that we do, many

actions which we do, which are non-verbal apologies of what we think are

faulty performances. I'll give you an example. I come in from this door here and suddenly see that the whole thing is in action. And I'm late and I cannot avoid being seen by you making my way to my chair. I've seen this many times in seminars in universities when students arrive late. They will do this. They'll come in and they'll go. I make myself ugly by going in order to anticipate your worst accusation of my stupidity. But I now have to get to the chair and cannot do it unnoticeably. So my approach to the chair has to be accompanied by a non-verbal apology. Why am I going on tip-toe? There is no way in which I can get to the chair silently. My surreptitious entrance is a way of saying if I had been able to get to my chair invisibly I would have done, but this is the best I can do. I'll give you one other example. You'll see this happen in Japan or it happens in Italy. Someone walking down the street. As soon as anyone walks down the street they know that there is an audience who might watch and see and detect a faulty performance. So I walk along and I accidentally trip. Now, watch this. Why do I go back to see how the damage is done? I go back to demonstrate to you my audience to show you the fault is in the floor and not in my walking. Another example you'd all know this. Can you get taxies by waving for it here? Watch people waving for a taxi and failing. Now why do they do this?

DE: If we just listen to

one typical scene of "La Taraviata" and one typical scene of “Falstaff”.,

there is a very quick answer for your question. One extreme example is from "Traviata", which is closest one continued Bel Canto for me. What I call un za za za, un za za za operas, which 95% of opera we can hear. Another extreme example is an opera like “Falstaff”. Unlike "Traviata",

when you walk out from the theatre after watching “Falstaff”, you

can hardly sing any tune of it. On the other hand, after watching

"Traviata", everyone can sing As another example, the opera one step toward to “Falstaff” is "Otello", which is also late Verdi opera before “Falstaff”. There we can feel the mixture of old Verdi and new Verdi, some un cha cha cha (Bel Canto Rhythm)but some non un cha cha cha ( Non-Bel canto rhythm). We have some nice arias and song like "Wine Song" by Iago and also we have lots of scenes more like “Falstaff”, almost Verismo and modern opera. This is more complicated and serious than the example I gave. It has lots more to do with different use of complicated rhythm, richer and different development in harmony and orchestration in “Falstaff” than in "Traviata", which is much more conservative and closer to Bel Canto style. Just I want to conclude the Verdi development. If "Traviata" started with relatively long overture, “Falstaff” like Puccini's "Madama Butterfly" goes straight into business. TN: Right into Life. DE: Right into life, right into realism. I think that is the big change. TN: I would like to have

one mystery clear about so-called Fuga. DE: First of all, Fuga is just musical term comes from Italian word"to run" because it really feels that one voice starts musical theme, other voices comes to run after him and all run together and together. Fuga is 2,3,4,5,and more musical voices or characters using one musical motive. Each voice enters a couple of bars after the previous voice started his motive. For 2 voices, we call it Canon, but it becomes Fuga when there are more than 3voices. Why is last Fuga of Falstaff is not called real Fuga. If we go back to Renaissance or Baroque, Bach Fuga, there are really tough and strict rules, that you can really analyze it. It is really mathematics. But for Verdi's Fuga, he started as a fuga and first motive starts and then second voice comes in, ladies come, everyone one after one came. We hear this musical theme but very fast and by the time when chorus comes in, we kind of loose the structure of real Renaissance or Baroque Fuga. But we get this running and everyone is gathering together with happy end theme of this one big serious-funny opera.

JM:I have to set it in the past, not necessary the past as Verdi visualized it, but I don't think it works very well in anything other than a sort of loose generalized abstract past. And that's why we have a very simplified set. It is based slightly on Dutch paintings for a simple reason. Not because I wanted to make it look Dutch but simply because the Dutch painters were the only people who in the seventeenth century gave us pictures of what the inside of ordinary houses looked like. The Italians didn't do it and the English didn't do it. The only people who did in Europe were the Dutch so we have very very detailed pictures of what bourgeois life was like in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. There are no Italian pictures of the interiors of ordinary people's houses. There are palaces (palazzi) but there are no pictures of ordinary bourgeois interiors. TN: Who is the Falstaff, what is his personality, did he run down from aristocrat or he was never aristocrat? JM: He expects respects,

he talks about honor, he no longer thinks he is worthy very much. 25 years

earlier, he lived according to honor, he doesn't live according to honor

now, but he has some proprieties left. I think it is very interesting;

the social anthropology of propriety, of cleanliness, of misbehavior is

extremely interesting. What do we hang on to, when we are unfortunate.

JM: I'm not absolutely sure. I think he's a confused character who has just escaped what could have been under almost any other circumstances, a very unpleasant ordeal. In fact in Europe in the sixteenth century, there was a whole culture of the torment of the deviant called Charivari (rough music) in which someone who had misbehaved was then mocked and tormented and sometimes in America in the nineteenth century lynched. He has escaped with his life and therefore he is relieved.

|